The Beach Boys are a significant and still-beloved part of American pop culture history, and it’s not hard to understand why. Songwriter Brian Wilson is universally recognized as one of the geniuses of American pop music, though like many other supremely gifted artists his life has been plagued by hardship. With Love & Mercy, director Bill Pohlad portrays two significant periods in the life of Wilson and though the film is inconsistent, it’s at times a riveting look at Wilson’s life.

The Beach Boys are a significant and still-beloved part of American pop culture history, and it’s not hard to understand why. Songwriter Brian Wilson is universally recognized as one of the geniuses of American pop music, though like many other supremely gifted artists his life has been plagued by hardship. With Love & Mercy, director Bill Pohlad portrays two significant periods in the life of Wilson and though the film is inconsistent, it’s at times a riveting look at Wilson’s life.

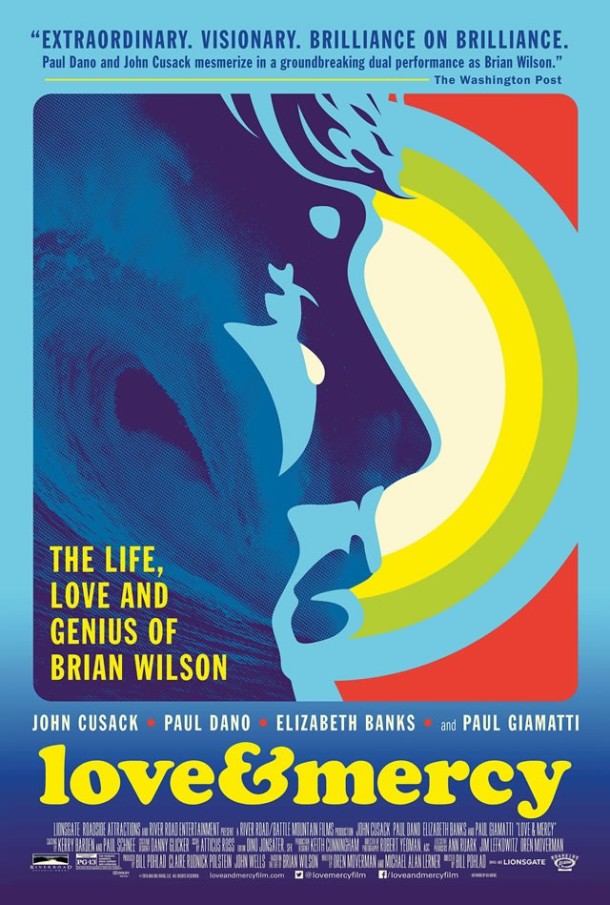

Unlike most recent movie biopics, Love & Mercy is not a “cradle to the grave” biopic of Brian Wilson (in part because Wilson is thankfully still alive). Because of that, someone unfamiliar with the Beach Boys’ history might become a bit lost. The film jumps between two critical parts of Wilson’s life: when he stopped touring as a Beach Boy in 1964 to work on his masterpiece Pet Sounds until 1969, when Wilson’s various personal problems almost entirely sidelined him from Beach Boys activities, and 1986 through 1992, when Wilson’s life was entirely controlled by controversial psychotherapist Eugene Landy. In the 1960s segments Wilson is played by an awestruck Paul Dano, while the 1980s Wilson is portrayed by John Cusack.

The main focus of the 1980s sequences is to show Wilson’s relationship with his eventual second wife Melinda (Elizabeth Banks) within the meticulously controlled environment he lived in because of his “treatment” by Landy (Paul Giamatti). Banks’ role doesn’t give her much to do beyond being the doting girlfriend who falls for Wilson’s wounded nature, though she is quite good in its limited nature. Giamatti is his sleazy best — think “Pig Vomit” in Private Parts — even if that mostly reduces Landy to a one-dimensional villain in the film.

In the past I’ve been critical of John Cusack’s reluctance to change his appearance for roles (his portrayal of Richard Nixon in Lee Daniels’ The Butler is essentially Lloyd Dobler with a gruffer voice), but Love & Mercy is an example of how Cusack can alter his body language to convincingly play an older version of Paul Dano’s character even though they don’t look much alike.

I was more engaged by the film’s 1960s sequences which show Wilson’s genius at work while working with Los Angeles’ famed Wrecking Crew in the studio, his relationship with his controlling father Murry (Bill Camp), and his working relationship with bandmates who are skeptical of his new direction, particularly Mike Love (a perfectly-cast Jake Abel). The in-studio sequences are filmed by Pohlad with a handheld camera, giving the shots a behind-the-scenes voyeuristic feel like a documentary. Dano portrays Wilson as a individual always on the verge of exploding, whether that be because of joy, frustration, fear, or creativity. The end of the 1960s sequence is heartbreaking — Wilson is clearly a sick individual, but he does not receive the help that he needs, which eventually led him to the dominating Landy years.

The last twenty minutes of the film meander as if writers Oren Moverman and Michael A. Lerner were unsure of how to end the movie. Wilson’s emancipation from Landy took several years, and the film takes a fairly pedestrian method used in most music biopics to depict the passage of time. Because Wilson’s actual musical comeback didn’t fully occur until 2004, the film ends with multi-paragraph title cards to explain everything that has happened to Wilson post-1992. It’s very awkward and it seems like there was a much more appropriate way to use the last twenty minutes of screentime.

However, for fans of the Beach Boys (and really, who isn’t?) who want to know more about Brian Wilson and the extraordinary talent that he possesses, Love & Mercy is a solid introduction to his troubled life. Though it doesn’t hit as hard as music biopics like Ray or Walk the Line, it’s definitely worth a watch.

Recent Comments