The concept of a pop “band” as we know it — a group of musicians who write and record their own music — might have began in the mid 1950s, but as The Wrecking Crew shows, that was not exactly standard throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. In fact, if artists wanted their music to sound as best as possible, they were better off calling on L.A.’s finest musicians — dubbed “the Wrecking Crew” — than relying on their own skills. This documentary tells the story of these Los Angeles studio musicians who played on hundreds of recordings.

The concept of a pop “band” as we know it — a group of musicians who write and record their own music — might have began in the mid 1950s, but as The Wrecking Crew shows, that was not exactly standard throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. In fact, if artists wanted their music to sound as best as possible, they were better off calling on L.A.’s finest musicians — dubbed “the Wrecking Crew” — than relying on their own skills. This documentary tells the story of these Los Angeles studio musicians who played on hundreds of recordings.

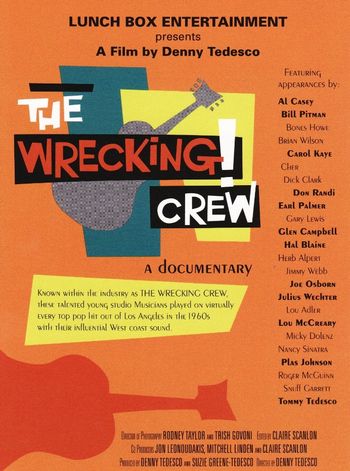

Director Denny Tedesco (son of Wrecking Crew guitarist Tommy Tedesco) began working on this documentary in the mid-1990s, but he did not screen it until the 2008 South By Southwest Festival. It took another six years to finish the film (including getting rights to the music) and for Magnolia to pick up the distribution rights. In that sense, it’s truly a labor of love. The long gestation period for this film means that it features interviews with subjects who are no longer with us (Dick Clark and Tommy Tedesco, among others) as well as Glen Campbell, a member of the Wrecking Crew before his own music stardom whose memories are no longer with him because of Alzheimer’s disease.

The Wrecking Crew was not a formal band — a funny moment in the documentary is when the members all offer different numbers for how many people were “members” of the Wrecking Crew ranging from 15 to 30, another funny moment is when they can’t agree on where the name “the Wrecking Crew” even came from — but a tight-knit group of about thirty Los Angeles musicians who were considered the city’s best studio musicians. The members played on hundreds of songs throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, including songs by the Ronettes (and most of Phil Spector’s work), the Byrds, Frank Sinatra, the Mamas & the Papas, the Beach Boys (aside from the vocals, the Wrecking Crew essentially WAS the Beach Boys from the mid-to-late 1960s), and, of course, the Monkees. The documentary highlights the fact that in the 1960s most people didn’t seem to care who played on what records, as long as the product was good. In fact, it deflates a lot of the criticism aimed at the Monkees, who are often ridiculed for not actually playing the instruments on their first two albums, when it’s revealed that many celebrated bands like the Beach Boys and the Byrds employed studio musicians in the 1960s (Monkees drummer/singer Micky Dolenz is one of the many interviewees in the documentary).

The Milli Vanilli lip-syncing controversy of 1989 is addressed more than once to show how much has changed in the music business in terms of fans expecting “authenticity” in later decades, perhaps at the expense of craftsmanship. However, there is plenty of evidence presented in this documentary that suggests that although the Wrecking Crew grew rich over being hired hands for their talents, there was some regret by the members that many of their recordings — especially instrumentals — made other people more famous.

One issue with The Wrecking Crew is the way it oddly felt slapped together despite being in production for eighteen years. The documentary jumps from member-to-member and topic-to-topic, and it doesn’t really follow a lineal timeline. Tedesco explores a topic like Brian Wilson’s work with the Wrecking Crew, veer off for a segment about his father, and then circle back to Wilson ten or twenty minutes later. It’s an odd way to present the narrative since it otherwise could be presented more directly. On top of that, some subjects are really due more explanation (the financial struggles of drummer Hal Blaine are worthy of a movie itself).

Perhaps the problem is that the subject is just so expansive and Tedesco has such intimate knowledge of it that it was hard to choose what to keep in the documentary and what to lose — in fact, maybe a mini-series would’ve been a better format for this work — but there is plenty to learn here and a great soundtrack throughout.

Recent Comments